Beneath the Service: What Law Firm Clients Really Buy

By Sergei N. Freiman

October 15, 2024 | 9-minute read

Client Services Project Management Process Improvement

Business of Law

Client motivations drive buying behavior in their pursuit of a valued goal. To enhance your services, focus on underlying goal facilitators and value activities that further attainment of the client's desired future state.

Earlier this year, my family and I got lost in the woods. We went to a hiking area 50 miles north of New York City called the Breakneck Ridge ― a place we had been to thrice. We took a familiar path, and I, feeling impervious to happenstance, didn't pay as much attention as I should have. Although being adrift in the woodlands was somewhat embarrassing, in hindsight, the experience was illuminating.

Law firm clients often find themselves in the woods too. Not necessarily lost ― although sometimes they are ― but certainly moving from point A to point B, from the current state of affairs to a different (better) future state. As my misfortune helped me understand, along the way, there are four motivations and ensuing four goal facilitators that can explain what clients are really interested in buying from legal practices.

Four Primary Client Motivations

Proposed by a clinical psychologist Richard M. Ryan and a professor in the social sciences Edward L. Deci, the self-determination theory (SDT) is focused on understanding how “human motivation is functionally designed and experienced from within, as well as what forces facilitate, divert, or undermine that natural energy and direction” (Ryan & Deci, 2017). The authors investigated human motivation in various contexts (including work setting) and identified three fundamental psychological needs: competence, relatedness and autonomy.

Having studied the SDT from the buyer-seller relationship perspective, I was able to identify four basic motivations that “prime,” or drive, client behaviors: control, belonging, mastery and exploratory curiosity. Working on a related subject of professionals' motivation during client engagements, I have stumbled on findings of two Harvard Business School professors who, to my surprise, have identified four similar motivations: defending, bonding, acquiring and learning. The two scholars claim: “we all are driven by four biological motivations” (Lawrence & Nohria, 2001).

This suggests that neither legal professionals nor law firm clients are exempt from four basic motivations. Hence, will positively respond to satisfaction, and negatively to frustration of these motivations.

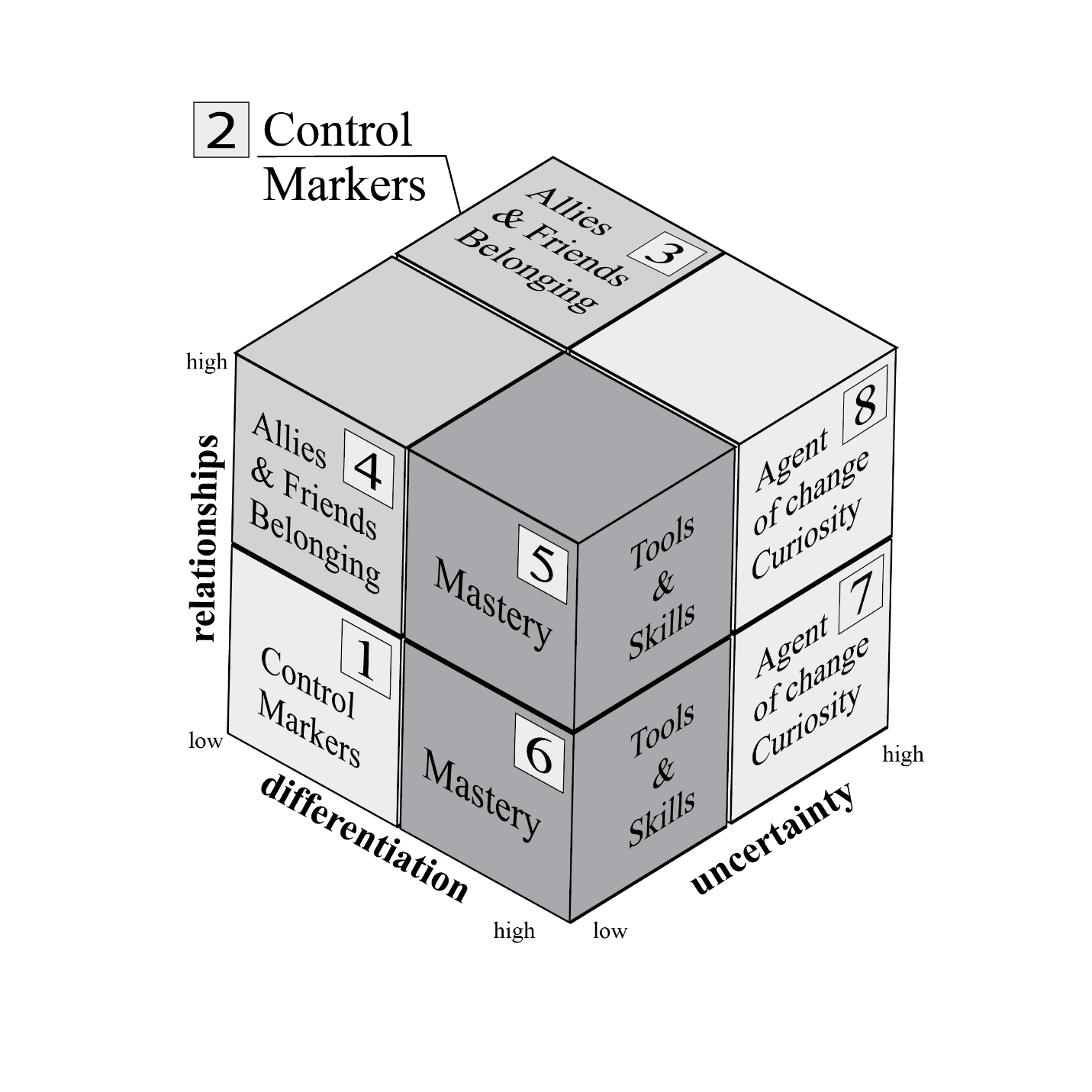

Other than priming behavior, motivations set up perceptual frames, and participate in goal setting. Hence, moving from current to preferred future state, clients will be interested in purchasing up to four goal facilitators: markers of progress, tools and skills, allies and friends and agents of change. Figure 1 exhibits the mapping of four motivations and goal facilitators. The three dimensions of this map have been adapted from Ryan & Deci's three universal psychological needs.

FIGURE 1. Mapping Four motivations and Goal facilitators

Four Goal Facilitators

As clients progress toward a desired destination ― a goal, or future state ― markers of progress inform and reassure them that things are going according to plan; that everything's under control. Motivated by sense of control, clients will be interested in paying for such markers. When clients can't deal with adversity or foes themselves, they will require allies and friends. Tools and skills are another valuable goal facilitator some clients will be ecstatic about. And just as precious is an agent of change. Let me illustrate by continuing with my opening story.

A typical hiking trail is equipped with various trail signs, or markers, that help hikers stay on track. Because I had long stopped paying attention to those markers en route, eventually we found ourselves off-track. Having made several failed attempts to find the trail, I felt everyone's anxieties kicking in.

Moving in all directions at once is rarely a prudent option. Because any direction is better than none, I chose a more promising path to follow. Shortly, we found the markers ― blue disks attached to tree trunks. Alas, we needed the white ones. Following down the blue trail we encountered the ultimate adversary―Pantherophis Obsoletus―a giant black rat snake. As thick as my arm and six feet long. At the time, I had no idea these were harmless to humans.

By the time we avoided direct confrontation with the snake, my makeshift staff shattered from pounding the ground in futile attempts to scare off the beast, and we were exhausted. Following the blue trail, we ended up at a private property. We had to turn back. At that moment, paying another visit to the monster's den didn't seem like a great idea. But there were no other predetermined routes we knew of.

We had two tools and one skill to put to good use: a trail map, smartphones with poor coverage and my amateur orientation skills. After some high-tension planning ― already breathing heavily ― we rushed a nearby hill. Dashing through an uncharted territory in an uphill battle was a treat in itself. Thankfully, at the summit we found a new path. By that time anxieties were at a peak too. A member of my group plumped down on a fallen tree trunk, head buried in their hands. After a five-minute rest, we went on.

When you 'd think it couldn't get more archetypal than that, eventually we found ourselves at the crossroads. There were three paths to take, and no time to explore — in a couple hours, the sun would set. Sure enough, resting in the shade was a lady of the woods: a fellow hiker who pointed us in the right direction. Thanks to her insight and advice, we changed our course, and in two hours were safely back in a nearby town.

Because it often gets overblown by marketing folks, thinking of clients' buying process as a journey may provoke some eye-rolling. However, the journey is real, and clients will actually be willing to pay for goal facilitators that aid them in getting to the desired future state. Those who've already been lost in the woods will be less “price sensitive.”

Six Value Activities to Create and Capture Value

Professors at the Norwegian School of Management formulated the concept of a value shop, which is applicable to professional services. Originally, the framework breaks value creation process into five primary activities (Stabell and Fjelstad, 1998). However, my analysis suggests the following six to be key: problem-finding and acquisition, attending, problem-solving, choice, execution and control and evaluation.

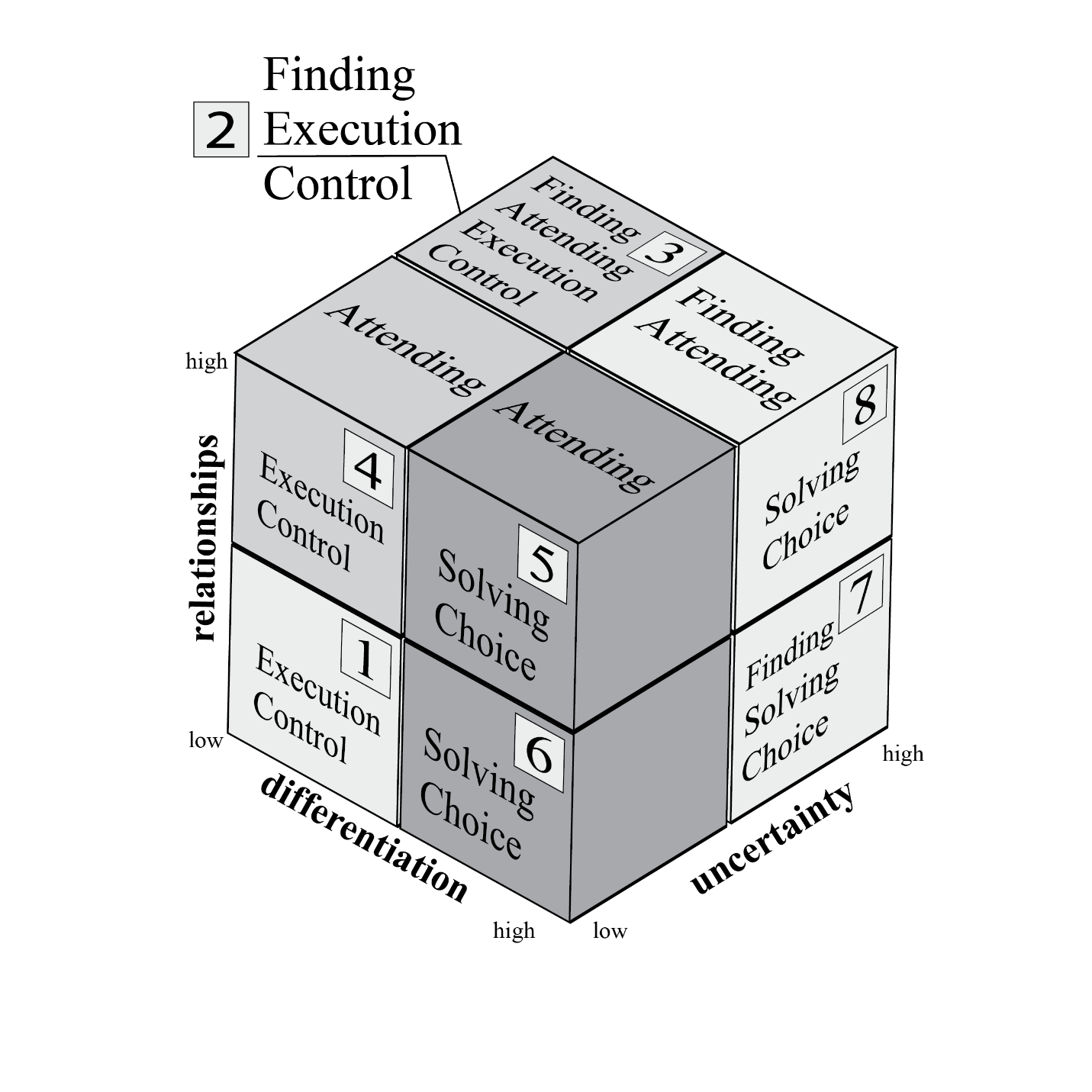

Figure 2 maps value activities onto the octants of Figure 1 map. Business developers and legal marketers should be able to infer client motivations from the value activities the client is eager to pay for, and vice versa. For example, if the client comes in self-prescribed ― knowing exactly what they want, how to do it and why ― it sends a strong signal that problem-finding activities are pretty much pointless.

Value activities are essential to great service offering design (SOD), prosperity of the practice and client satisfaction. These activities are those which clients are often exposed to in real time during service provision. Hence, they are often perceived as more valuable. Law firms may intentionally select and adjust the intensity of value activities, thus fine-tuning service offerings, which allows them to capture more value for the practice while simultaneously creating more value to clients.

FIGURE 2. Map of Value creation activities

To read this map properly, note that all six value activities may be important to the client. In addition, clients may be equally motivated by several motivational forces simultaneously (e.g., control and mastery). However, when push comes to shove (e.g., the fees must go down) value activities pertinent to their respective octants are typically the ones to be altered last.

How Can Legal Marketers and Business Developers Apply These Concepts?

- You may want to use goal facilitators as a framework for your marketing communications. For example:

- As markers of progress, your firm may highlight availability of: client dashboards, checklists, gauges, reports, task boards, progress status ― assets that cater to clients' sense of control.

- As tools and skills: client training and coaching, and access to special resources (e.g. databases, case management software, or contract management system, document templates, etc.).

- As allies and friends: insights, professional gossip, intuitions, protection from adversity, rapid-response teams, conflict of interest prevention, roundtables with peers, etc.

- As agents of change: new business opportunity exploration, advisory, business introductions, anticipation of and response to major industry shifts, novel approach proposal, etc.

- At the client qualification stage, you may be in the best position to assess which value activities will be important to the client. This will allow attorneys to adjust their workflow, which inevitably impacts profitability of an engagement and overall fees.

- Because functional deliverables aren't the only criteria of best client fit, you may want to inform attorneys about client motivations, priorities and expectations, juxtaposing them against both your attorneys' (functional) capabilities and (emotional) willingness to get involved.

- Participate in designing per-packaged solutions. With fewer ad hoc activities, teams are typically more effective and productive. Having well-designed, readily available packages on client pitches allows attorneys and business development (BD) staff to swiftly pick the most suitable one and adjust the components on the fly — without having the necessity to sacrifice quality or fees.

- Similarly, understanding client motivations, goal facilitators and value activities provides a framework for proposal drafting. Based on preliminary diagnostics, consultation, client type assessment or whatever means of client qualification your firm employs, you can help streamline RFPs.

- Being on the front line allows you to keep track of most current changes in client preferences. The more proficient you get with identifying client needs through vetting, qualification, diagnostics, behavioral tells, as well as knowing which levers to pull in response to change in demand, the more valuable you are to the firm. Because you will have a front seat and a hand on clients' pulse, you will be in a better position to elevate your role in firm's business strategy formulation.

- Attorneys and professionals will be the ones to execute the bulk of the service. Because word-of-mouth will always be a significant marketing channel, it is paramount to match (and aim to exceed) client expectations. For such probability to increase, it is vital to ensure professionals can, want and will commit to particular service provision activities. BDs and marketers can take up a role in bringing professionals together to formulate the most exciting type of client work most professionals will be excited about.

- As the client work unfolds, both environment and client preferences might change. Knowing which value activities and goal facilitators may become important will allow for quicker response.

- The aforementioned framework may help during market shifts too. While demand for functional deliverables is likely to vary over time, the underlying four motivations and goal facilitators are universally constant. When the time comes to reconfigure your firm's service lines, you will have your primary SOD toolkit ready. Which makes you evermore valuable for the practice.

Conclusions

Today, we've covered a lot of ground in one fell swoop: four motivations, four goal facilitators, six value activities, and a handful of practical tips. Beneath the surface of every service offering are motivations, goals and expected value. Alas, this isn't an exhaustive list of all things pertinent to great SOD. If you intend to do something with service lines at your practice, understanding client motivations is a great place to start.

References

- Lawrence, P. & Nohria, N. (2001). Driven: The Four Drives Underlying Our Human Nature - Driven: How Human Nature Shapes Organizations. Harvard Business School Working Knowledge. October 9, 2001.

- Ryan, R.M. & Deci, E.L. (2017). Self-Determination Theory. The Guilford Press, pp.10-11

- Stabell, C.B. & Fjeldstad, Ø.D. (1998). Configuring value for competitive advantage: on chains, shops, and networks. Strategic Management Journal, Vol.19, pp. 413–437.